Tuesday, September 11, 2001, was the day I became a writer. I was living in Los Angeles and had written a top-rated network TV show, the International Guinness Book of World Records and had “helped in the writing” of Kirk Douglas’s best-selling autobiography, The Ragman’s Son. But now I had a contract to write a book by myself. It was about the history of food, and I was calling it Cuisine & Culture. I made a cup of chamomile tea and was at the computer at about 7:20am to do what Hemingway called “facing down the white bull” – that page with no words on it.

I had the TV on in the background and was channel surfing. Most of the stations were doing regular programming but some were showing a promo for a disaster movie about a high rise. I looked for the ribbon at the bottom of the screen with the info about when it would air. No ribbon. I turned on the volume. Then I did what everybody else in America did that morning – I jumped out of my chair and I screamed.

I knew instantly that because it had happened so early, all the bakers were dead. They show up ungodly early. Then I downloaded the entire website for all the restaurants because I knew they were gone, too. I had attended the wedding of two college classmates at Windows on the World, and I wanted people to know about those glorious restaurants. So I sat back down and wrote about them—the first thing I wrote in the first edition of Cuisine & Culture, 2003. This is adapted from the first three editions:

***At the southern tip of Manhattan stand the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center, the tallest buildings in New York. They have their own zip code because every day, 50,000 people from more than 60 countries file into them to work and to visit. And they all have to eat.

At street level is the Big Kitchen, a food court with Ben & Jerry’s ice cream, Mrs. Fields cookies, Pastabreak, the Italian deli Sbarro, and others. On the 106th and 107th floors—the very top—of One World Trade Center, 79 staff members are in the kitchen, because 500 people are attending a business breakfast.

George Delgado, head bartender at the Greatest Bar on Earth, is sometimes in but he worked until almost 2:00 a.m. Unusual for a Monday but Dale DeGroff, aka “King Cocktail,” had conducted a tequila tasting. Carmen Newman, coordinator of the $1 million wine collection in the school run by Kevin Zraly, would usually be in, but a series of classes has just ended, so she and her husband are on their way to the airport for a vacation.

Executive Chef Michael Lomonaco plans to take the 58-second elevator ride up 107 stories after he gets his eyeglasses. But he will never get into the elevator, because the building is on fire, filled with exploding jet fuel. The nearly three thousand people who were killed that day will never be seen again except in pictures on telephone poles, walls, and makeshift bulletin boards in Grand Central Station and all over New York: Gomez, O’Doherty, Kawauchi, Benedetti, Snell, Gilligan, Koppelman, Cho, Hidalgo, Andrucki, Jones, Mirpuri, Metz, La Fuente, Amanullah. Samantha.

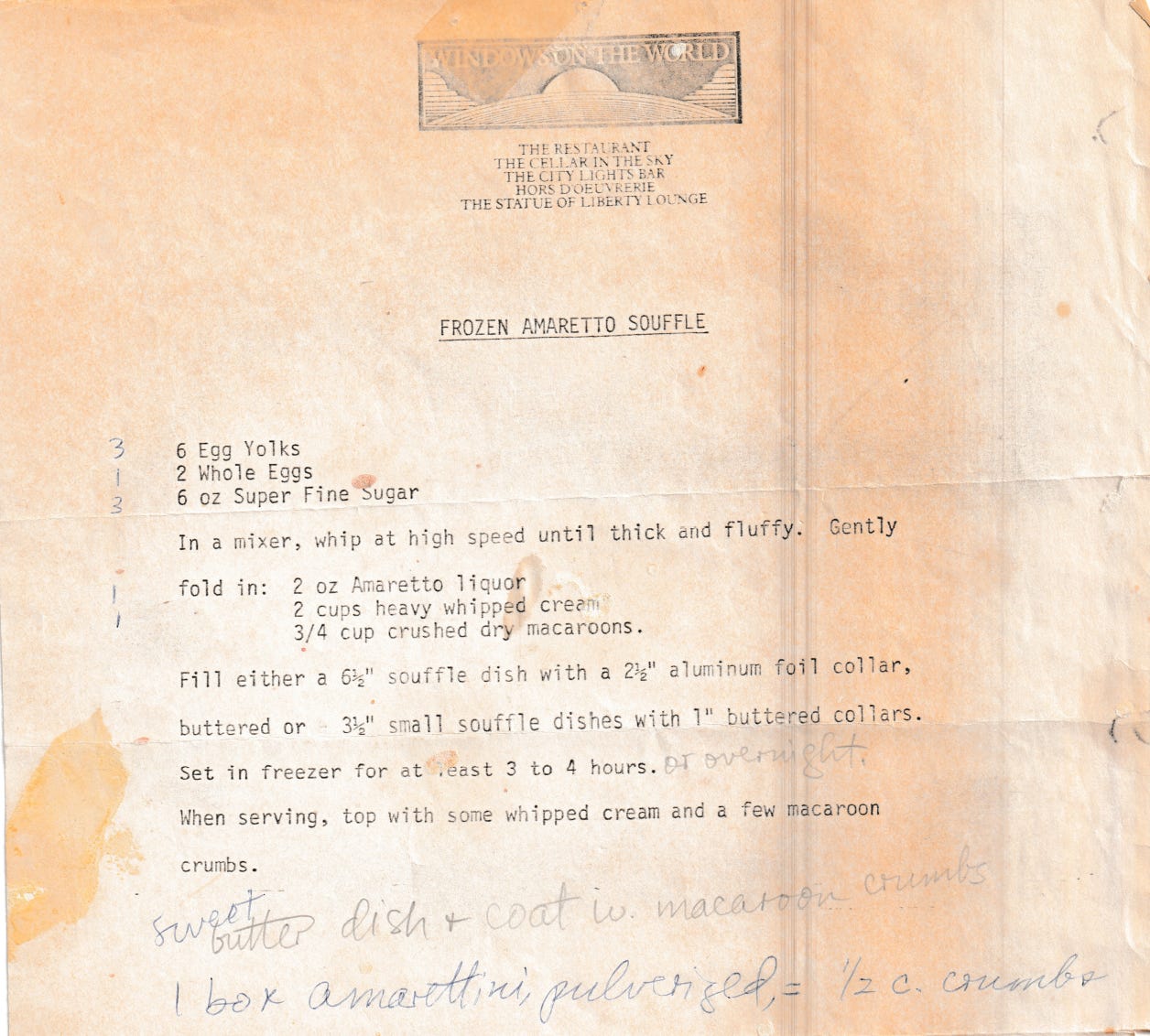

There is a special place in my heart for Windows on the World. I got one of my favorite recipes from there—chef Nick Malgieri’s Frozen Amaretto Soufflé. It lists the restaurants when the towers first opened: the Restaurant, the Cellar in the Sky, the City Lights Bar, the Hors D’Oeuvrerie, and the Statue of Liberty Lounge. NOTE: This original recipe was made with raw eggs, which the FDA says are no longer safe to eat. In his book Great Italian Desserts, Chef Malgieri changed the recipe to a semi-freddo with eggs cooked over simmering water, like a zabaglione.***

In 2015, I wrote about Windows again, in Savoring Gotham: A Food Lover’s Companion to New York City, edited by Andy Smith:

***Born in the bicentennial, 1976, Windows was a Cinderella story. With New York City on the verge of bankruptcy, critics reviled the Port Authority’s $950 million World Trade Center complex. Then Windows became the jewel in the crown of New York restaurants created by Joe Baum and Michael Whiteman.

The Hors D’Oeuvrerie served smørbrød to sushi. At lunch, Windows was a private club, open even to women, unlike other Manhattan clubs at the time. The Grand Buffet ($7.95) contained Madras chicken curry, salumetti, six kinds of herring, and smoked chicken with Moroccan lemon relish. Chef consultant Rozanne Gold created a show-stopping white clam risotto with poached lobster napped in green sauce.

In 1997, Chef Michael Lamonaco took over. His “American spirit” cuisine reflected America’s new pride in its regional, creative, culinary identity: California artichoke salad, pan-fried Catskill trout, rib eye of American buffalo with Vidalia onions, and pumpkin cheesecake. Wild Blue, the chophouse, served sauteed Hudson Valley foie gras with nectarine and plum compote, and American lamb T-bone chops.

Windows on the World was the quintessential New York restaurant: it took diners to the edge. Trend-setting cuisine vied with 90-mile views. It lived up to its acronym: WOW.***

The view was indeed spectacular. In the harbor, directly below Windows, the Statue of Liberty raised her torch up toward you. The Zagat Guide said it best: Windows on the World “put diners close to heaven.” WOW. RIP.

I knew Carmen in 1987. She loved the WTC, and I believed that she was destined to always work there in some capacity. After the attack, I always dreaded what happened to her. I finally got the nerve, and was able to discover, I believe through your original article, that she was off that day.

Thank you so much for writing this.

Thank you for writing this, Linda. It’s such a unique and poignant perspective.